Guidebook to Installations of the Jovian Confederation - Chapter 4

Chapter 4 Cologne: An Industrial Cylinder

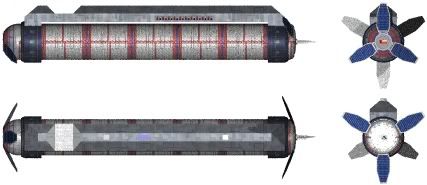

4.1 Basic Layout

- Rotational Period: 73.7 seconds

- Outer Cylinder Radius: 1.6 km

- Inner cylinder radius: 1.35 km

- Habitable surface area: 195 sq.km

- Population: 2.63 million

- Density: 13500/sq.km

- Overall length: 27.6 km

- Maximum spine height: 3.2 km from rotational axis

- Operational date: December 15, 2140

- Cylinder number: 27

- South Polar Comm Cluster

- Gee Level

- Environmetal Machinery

- Factory Spine

- Cylinder Environment

- Sunline

- Class-A Autofac Bay

- North Pole Dock

Cologne’s layout derives from two paramount facts. First, it was planned from the beginning as a dedicated industrial colony, catering to the growing needs of the Olympian state. Just as important was the newfound confidence of the designers. With an entire generation of colony cylinders under their belt, they were finally able to take some small, calculated design risks. The result is a mature design, more efficient and specialized. Cologne was built as one of the first colonies expected to be a city in a nation, rather than a city-state of its own.

The new design’s most prominent feature is the massive factory spine, more than thirty-five percent of the station by mass, and much more than that in terms of GDP. With the spine hovering just a few tens of meters above the rotating cylinder, the thermal radiators needed to be moved near the colony’s poles. The docks were also been rearranged, with separate facilities on the cylinder and factory spine. The south pole is now almost entirely dedicated to communications equipment and elements of the colony’s electrodynamic array. Cologne is typical of industrial designs in Olympus. There are perhaps three or four major variations on the theme, but for the most part the design had proven so successful that it became ubiquitous.

4.1.1 The Cylindrical Plain

Cologne must import much of its food. When it was designed in 2122, it had become clear that a stable human presence in Jovian space was not a pipe dream, in danger of collapsing under the waves of refugee immigration from the inner system. Being a closed system was no longer a virtue, and just as the factory spine represents the strength of this approach, the interior environment of Cologne showcases the weaknesses

The civic planners left next to no room for agriculture on the surface, instead they attempted to maximize the living space directly available to each citizen. This plan was also based on unrealistically high projections for the automation of the factory spine. When these projections failed to pan out, the opportunities for more and more workers in high-paying industrial positions created more immigration pressure. Unfortunately, the attempt to maximize personal space failed when increasing immigration drove the population density through the roof. Rather than seeing a colony with less than ample commons, government bureaucrats saw a colony with excessive living space per person. When they were done equalizing that discrepancy, Cologne was severely overcrowded.

Without the public parks and dual-purposed agricultural lands of the first-generation colonies, Cologne, and a number of her fellow industrial cylinders, were in trouble. These harsh times helped forge the stereotypical Jovian mindset where space is paramount. The population peaked in the 2160s and Cologne has since aggressively moved to establish parks and other public facilities as space allowed, but it is still behind the standards set by most other cylinders. Later industrial cylinders also corrected this problem, establishing public lands at the outset and encouraging a portion of their worker base to commute from other colonies.

Circa 2210 Cologne’s interior surface area is 50% residential, 25% commercial and 15% ecological. With such a small percentage of its surface area allocated for ecological use much of the atmospheric concerns -- gas balance and evapotranspiration -- are heavily aided by machinery. While larger in length than any one of the segments of the first-generation cylinders, the smaller radius of Cologne and her fellow industrial stations does not allow for much in the way of weather. Usually the closest thing that the average resident will observe is the Coriolis-distorted form of a high-altitude cloud.

Cologne uses a continuous lighting sunline with four strips. The design was cutting edge at the time of construction, and to this day reproduces most elements of the solar spectrum very well. The diameter of the illuminating portion of the line is thirty-five meters. However, this balloons to one hundred meters where the sunline meets the supporting struts that rise from the cylinder floor. Inside these vast caverns the lightest of the microgravity industries find low-rent facilities.

4.1.2 Thermal Radiators

While vastly lighter and thinner than the cylinder or factory spine of the colony, the thermal radiators have just as large a visual footprint. They rotate with the main cylinder and are angled in, reducing the acceleration on the outermost elements. The mounting is somewhat flexible, allowing the tethers that link to the radiators to slightly adjust the angle, and with it control the rotational period of the colony. This is used only slowly over the years as the cylinder loses energy to interaction with the factory spine. Once the radiators have exhausted their few degrees of movement they are relaxed while thrusters spin the station up to normal again.

The efficiency of these radiators allow the industrial stations a much greater energy budget than their early predecessors. Still, they can do only so much for the factory spine, to which they are not directly physically linked. Some heat is exchanged between the spine and the cylinder and radiated normally, but for the most part the spine must take care of its own thermal budget. A portion of the volatiles that would otherwise be used in the fabrication of goods must be set aside for venting to make up for this deficiency.

4.1.3 Communication Towers

Between the spine and the thermal radiators little space is left for the classical communication towers of the first-generation cylinders. Many engineers consider this no great loss; they were uncomfortable placing the communication towers in territory greater than one gee in the first place. As a result Cologne’s south pole hosts an extensive array of communications gear. The north pole has a few smaller towers, as does the factory spine, but the south pole handles the vast majority of communications traffic. This location makes the equipment extremely easy to service, but it deprives the colony of a south polar dock.

4.1.4 Factory Spine

In a very real sense it is the factory spine that gives the industrial station a reason to be. The proximity between highly skilled human workers and the advanced fabrication equipment of the spine is lucrative indeed. With advanced artificial intelligence barred by the Edicts, human workers are in high demand. While a good portion of the labor on a factory spine is automated, the flexibility of human response remains useful, both on-site and with real-time telepresence.

Besides the direct fabrication of labor-intensive materials and consumer products, factory spines also serve as light shipyards. While large interplanetary vessels are always constructed at dedicated free-floating facilities, smaller craft, launches, shuttles, cutters, orbital transfer vehicles, and to a lesser extent, exo-armors are often produced in factory spines. Industrial colonies often serve as a place of employment for workers from the regular shipyards who require a few months back under normal acceleration to keep microgravity symptoms at bay. Conversely, these light shipyards also serve as a training and recruiting ground for those who will be going onto a true shipyard for the first time.

The last of the primary tasks of an industrial cylinder is the construction and servicing of autofacs. Von Neumann machines are banned by the Edicts almost as strongly as extensive human bioengineering. Autofacs are extremely profitable, and in the face of the continuing military build-up the Jovian government is offering a number of security guarantees designed to assure that a massive industrial capacity exists regardless of the economic need. As a result investors are finding autofacs an even better choice all the time. The dorsal surface of the factory spine is littered with bays where autofacs of all sorts can be constructed. In an average month Cologne’s spine produces three small autofacs and one medium one. Truly massive class A autofacs are constructed on an irregular basis. Indeed, the central section of the spine almost always contains a moored class A, save in the rare case that one is actually under construction at that time. When there is no such construction in progress the owner of the autofac constructed previously will usually prefer to enhance the efficiency of his investment by hiring a relatively large staff from the colony to run the autofac. Only reluctantly will the owner accept the diminished productivity that comes with letting the factory loose.

4.1.5 Docking Areas

Cologne has three major docking facilities. The first is the north polar dock, serving the entirety of the cylinder. It is an enhanced and refined version of the axial docks used in the first-generation cylinders. The interior chamber is much larger, capable of docking large passenger liners such as Inaris on the far wall. Smaller vessels are diverted into low-gravity slips to either side, and multiple large ships can be handled by extending mooring arms into the centerline. This is rarely used to accommodate more than three large vessels, as the ships will then have to wait for the ship behind them to depart before they can leave.

No less important are the cargo docks on the dorsal surface of the factory spine. These docks take advantage of the clear approach that ships approaching from ‘above’ the colony have. Supplies are received and products shipped through these docks. The same approach and departure lanes are used by the autofac moorings and light shipyards for their respective products. The incredible mass of the shipping commonly accepted at these ports is such that each docking is a monumentally slow affair, to minimize risk and any inadvertent momentum transfer with the colony. The dorsal spine docks also serve the JAF, which owns a cluster of them at the southern end of the spine. JAF non-combatant and non-essential ships often put into dock at industrial cylinders for minor repairs and system upgrades. Warships do not because their systems are much more specialized and not suited to yards tooled for civilian systems.

4.2 History of Cologne

Cologne was born as one thing, and has lived as another. That dichotomy is the reason that Cologne is considered a paradigm for the success of the Jovian charter system. When Cologne was first chartered it was by the largest and most stable cult ever to develop in Olympus. They registered their organization as the Jovian Technophilic Society. Under the guise of a loose band of hobbyists, they were actually a religion structured like a business, or a business with the trappings of a religion, depending on who you ask. The one clear thing was that the were a clear and distinct community within the Confederation, separated by rituals and customs designed to drive a wedge between members and mainstream society. Public nudity was one such custom, the avoidance of naturally grown foods another. More materially relevant were doctrines on medicine, which demanded the most proactive interventionist measures possible. This brought them into conflict with the government on numerous occasions where physicians and government guidelines declared certain medical procedures that JTS members desired for their minor children to be unnecessary and possibly harmful. They may have been harmful to the children, but the publicity certainly wasn’t bad for the JTS, which continued to draw members from the fringe of Jovian society.

Membership of the JTS had swelled to more and a quarter of a million people by 2120, and that in an Olympus far smaller than today. The problem could not be ignored. The governments of Olympus and the Confederation came to agreement on a bold gamble to restore the social stability of the state. An obscure colony charter request from the JTS would be granted. Government projections showed that the JTS would be swallowed alive by the first wave of immigrants, and that is exactly what came to pass. No other colony would see its charter bent and abused in the same ways. The planners of the colony, then known as Fulton, knew full well the challenge they faced and were not about to deny themselves any tool in pursuing their ends. All this damage vanished, nearly without a trace, within five years of the colony opening. It was that year that the JTS stopped being even a tourist attraction. Cologne was too successful, and the Jovian political system too robust for such manipulation. Most likely either the economic boom, or the will of the majority could have spoiled the JTS plans alone. While the occasion has not arisen since to destroy a similar group in this fashion, the Jovian government does hold the contingency at hand.

4.2.1 Visionless Vibrancy

Despite the population pressures that plagued Cologne in the 2160s and 70s, the colony has never known any true hardship. Not only was the Confederation stable, but it was growing, and in great need of the services of an industrial cylinder. Even as the population blossomed jobs were plentiful. Over the decades leading up to 2210 there has been a slow contraction of the job market on Cologne. This is has not caused any real difficulty, there are still many jobs available, but the urgency has been reduced, and the fraction of jobs which are suitable for full-time employment has fallen. This has led to a large percentage of the Jovian population being in a position to work only irregularly, when their personal finances require it.

There is no guiding principle to Cologne’s existence. The population is largely content to enjoy what it has without grasping for more. This is where Cologne is most emblematic of the malaise of success that seems to have come over much of the Confederation. While some of the older vivariums seem to have redirected their energy into petty bickering and internal politics, Cologne has remained curiously quiet.

4.2.2 Politics

Cologne has never shared the isolation of its Olympian neighbors. This is largely due to the massive contingent of Martian immigrants. Some came directly, fleeing the territorial expansion of the Martian Federation in the times of flux that followed independence, others were from the Federation itself, political refugees. While many of these displaced persons found refuge in the Free Republic, some held such a dire view of Mars’ future that they chose to emigrate to Jupiter. The Confederation was never hostile towards these refugees, but it felt very much empowered to find them permanent housing in its own good time. These simple delays led to a Cologne where former Martian citizens were entirely over-represented.

Political scholars have often likened Cologne to Miami of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Cologne is also a community of exiles that polarizes the context in which a great power, in this case the Jovian Confederation, views a minor power. It is this three sided relationship, between Mars, Cologne and the Confederation at large that defines the character of Cologne’s politics. Where everything else is concerned Cologne usually votes with other industrial colonies, but it has a unique political axe to grind.

Not only do these issues affect the positions of representatives sent to the state and confederation governments, but the otherwise unremarkable local politicians will often use their office as a soapbox to discuss the evils of the Martian Federation. It is widely believed that Cologne is home to a number of Jovian citizens who have aided the Free Republic, and non-aligned terrorist organizations, over the last several decades. While these contacts are almost entirely illicit, Cologne is the only place in the Confederation where the authorities have so blind an eye.

4.3 Major NPCs

Cologne has a diverse population, all the more so for the rarity of local flavor. The five NPCs below are all important to Cologne, be it politically, economically, or culturally. More than that they are the fulcrums about which Cologne’s society will evolve. They are likely candidates to have interaction with player characters.

4.3.1 Theodore Kohlmann

- Age: 64

- Hair: Grey

- Eyes: Blue

- Height: 187 cm

- Weight: 112 kg

Confederation politics are almost always too tepid to qualify as exciting, but Theodore Kohlmann has energized an extremely loyal voter base with his unique approach. His most remarkable feat is having remained a nation-wide figure in politics for three decades, with a mere six years in office. When he first stormed to the public’s attention it was in a blitzkrieg run for a council seat on another station entirely, Sisyphus. That station was gripped by a rare economic crisis, one which Kohlmann quickly turned around. While only one councilor among many at the time, he had virtual complete control due to a sweeping election mandate. When he chose to stand down at the end of his first two year term, it shocked political observers. Rarely in the history of the Confederation had a single individual held such power on a colony, and he walked away from it. Soon thereafter he emigrated to Cologne.

Twice now he’s run for office from Cologne, and twice he has won. Each time he implemented a specific goal and left at the end of his term. Each time he was untouchable during his term. In these three short terms he’s earned a reputation as being invincible. Even as he sits on the sidelines for a span of years, the shadow he casts is long. His weekly editorials on the SysInstruum are widely followed among both the political elite of the Confederation, and his loyal supporters in the electorate.

Currently Kohlmann is eight years into his second marriage to Maria Saba, a locally famous former athlete. He has embraced Cologne as his new home with open arms. His politics, firm and nationalistic to begin with, have now long rung with the strident tone peculiar to Cologne. Even for an Olympian politician his zeal for intervention in the politics of the solar system is extreme.

4.3.2 Olga Moratonovich

- Age: 26

- Hair: Black

- Eyes: Green

- Height: 164 cm

- Weight: 53 kg

Olga Moratonovich is a young, up and coming businesswoman. Currently she heads the division of Hephaestus Industrials in charge of renting excess space in the laboratories and yards of the Cologne factory spine. The work is low margin to say the least, but Moratonovich is making an effective administrator. She is responsible for the aggressive marketing of the latest ‘lab assistant’ expert systems. These programs had to undergo extreme scrutiny before it was decided that they did not violate the Edicts against artificial intelligence. With all the publicity that arose from those inquiries, Hephaestus has been generating record sales and rentals. The new systems allow extremely sophisticated experiments to be run with minimal human intervention. Moratonovich is currently engaged in rebuilding the company’s physical infrastructure to make the best use of the new technology.

Seemingly manufacturing additional time at her whim, she is also very active in the social and cultural circles of Cologne. She is a frequent guest at political dinners, where she has allied herself with the most strongly pro-business elements of the colony’s council. She has strongly denied having political aspirations of her own, and all signs point to the truth of this. Moratonovich has also managed to become the front person for several cultural events funded by Hephaestus, giving her the unearned reputation as a friend of the arts.

She defines her relationships with people with extreme care, not to avoid confusing her personal and business lives, for she does not make that distinction, but to more accurately deal with the other person. While she may appear genuine, only her annoyance at being detained by insignificant people truly is. When her friends have confronted her about her slavish devotion to Hephaestus, she does nothing more than assure them that she believes there is more to life than corporate success, but she steadfastly refuses to say just what that might be. Even her friends are puzzled, unsure if this means that she truly does not know what else matters to her, or if she simply does not want to talk about it.

4.3.3 Andrew Behr

- Age: 43

- Hair: Red

- Eyes: Brown

- Height: 180 cm

- Weight: 84 kg

Andrew Behr is one of the leading artists of Olympus. His signature art form is attention-responsive visual media. Each piece must be viewed by one observer at a time. A compact laser tracking system monitors that persons eyes, both direction and depth of focus. With that information the system consults a program that alters the displayed imagery in accordance with the artist’s wishes. With the use of ‘smart’ materials almost any object can become the subject of such a piece. Behr’s works include items designed to look like paintings, vases, chairs and pizzas.

Behr has only been at this particular form of art since 2209, prior to that he was primarily a landscape artist who occasionally dabbled with cellular automata. Then he spoke to an acquaintance working at Jovian Optics, and soon the notion of using HUD laser tracking technology to create interactive art was born. Behr’s fame has made him one of the few artists allowed to use a significant amount of space in his works. He has been commissioned several times to create interactive statues for Cologne, including replacing the obligatory statue of Alfred Decker with one of his own. That figure is considered controversial for its unflinching depiction of all the character traits the historical giant exhibited.

Behr has a wife who works as a government functionary, overseeing the legal aspects of certain contracts between the Confederation government and private business. After five years of marriage she is still very much in love with her husband. He in turn has not done anything to be undeserving of her loyalty, contrary to many artist stereotypes he is extremely emotionally stable and jovial. He has one grown child from a previous marriage, Roberta, who has had many jobs since coming of age but has never settled into any one career path, not an uncommon lifestyle among the under-employed Jovian population. While not reclusive, Behr does not seek to be in the public eye. Usually he goes about his affairs quietly, and doing only the minimal number of publicity appearances when a new gallery of his work is opened.

Unlike so many other forms of Jovian art, it is impossible to properly appreciate attention-responsive material via the SysInstruum. It has long been the rumor that Behr is working on a project that will both convert the essence of his material, and create a new way of interacting with it for the SysInstruum. Many art critics have taken a dim view of one recent trend, the practice of creating only a minimal algorithm for a piece, offering up its changes only after long study. The practice has numerous detractors, but a vocal group of critics declares it to be genius, forcing the viewer to appreciate the underlying value of the subject before being rewarded, and hopefully surprised by the twist the algorithm puts upon it.

4.3.4 Jonathan Crenshaw

- Age: 57

- Hair: Black

- Eyes: Brown

- Height: 175 cm

- Weight: 102 kg

Jonathan Crenshaw is the CEO and majority owner of Perijove Transport, one of three major shuttle services on Cologne. He came into this position after starting as an OTV pilot in a rival company. Eventual he became an administrator, dealing primarily in the logistics of a certain set of assigned cargo and passenger routes when Perijove made him a better offer. Five years after he took the position with Perijove he inherited it from the previous owner, with whom he had become close. His leadership has been undistinguished, but that has served Perijove better than flashy, radical decision making. The economic environment has been conducive to the company’s growth, and the last twenty years have seen such an increase in the personal mobility of Jovians, and in the amount of cargo coming in from the other solar nations, that it would be difficult for a company in Perijove’s line of work to be less than prosperous. Market share has been eroded somewhat, but with the size of the market growing explosively this has hardly concerned Perijove.

Crenshaw himself is pleasantly absorbed in the task of running the business, though his definition of absorbed seems less than rigorous to many of his subordinates. Nearly everyone in the tier beneath him has their own radical plan to revitalize the company and make it the prime player in the shipping markets of Cologne and nearby Olympian colonies. Indeed, it is true that Perijove possesses numerous strategic advantages that could make such a move successful, but Crenshaw has shown no desire to reinvent the company. The other investment partners are happy enough with this, none of them invested in Perijove expecting the strong returns that they’ve received so far. A low risk policy is perfectly fine with them.

What the investors and vice-presidents do not know is that Perijove has taken an active role in semi-legal support to the Free Republic. While it rarely breaks the law outright, it has systematically altered the manifests of items that might otherwise have been indefinitely tied up in red tape. Jonathan Crenshaw’s mundane face masks the very real fact that he is very much involved in international politics. With the recent outbreak of hostilities on Mars, it is very likely that he will step up his involvement, possibly supplying entire weapons systems.

4.3.5 Jane Skorsen

- Age: 29

- Hair: Brown

- Eyes: Blue

- Height: 172 cm

- Weight: 61 kg

Running the docks on a station as busy as Cologne is a major task indeed, and assistant dockmaster Jane Skorsen is more administrator than traffic controller, but that removal is no respite. As dockmaster she is responsible for maintaining the docking facilities, establishing queues, and handling custom inspections. As dockmasters go she’s extremely good. Her career is really just getting started, she was promoted to her current position in 2211 after three years as a traffic controller. A handful of times she has found herself shaking her head after a strange and awkward conversation with a fellow employee, she still doesn’t quite know what they were trying to get at, but she knows it was being put to her in a painfully oblique way. The truth is that they have tried to subtly bring Skorsen into the ring of collaborators with the Perijove smuggling operation. Skorsen’s rigid propriety has allowed her to totally overlook their probes, and it is thought far too likely that she will soon stumble onto the operation herself.

4.4 Location: Microgravity Lab

Microgravity environments have a multitude of uses in the Confederation, and not all of them dominated by huge industrial conglomerates. Many small organizations and even some private citizens can find them useful as well. To fill this market small microgravity experiment and fabrication palettes have been designed, and these in turn situated in rooms that are something like morgues, with all the walls lined with drawers containing the palettes. If a Jovian is to have contact with a microgravity lab, this is the most probable kind.

4.4.1 Description

Each lab is built around a central access area. Depending on the terms of the lease the access area may be accessible to the leasing party, or it is used only by the facility staff, who will perform any necessary maintenance or experiment retrieval. Since the very basis of this sort of business is to cater to the wide variety of miscellaneous microgravity uses, there is no one standard palette size. Usually any given lab has slots for several different types. The result is still very ordered, the north wall may mount ten by eighty by five centimeter bays, designed to take a brace of ten microcrystal growth mechanisms while the south wall contains no more than five massive bays for metal-alloying. Usually the variety is more restrained, yet the most efficient rental labs take up all their volume in the money-making palettes and not in the large access passages needed to move the largest palettes in and out.

Each palette type is also configured for a particular set of power and resource couplings. In most cases electrical power is provided in the cost of rental, but additional resources are paid for on the basis of usage. Palettes will commonly need electricity, a network hook up, and most rarely, cooling water. Additional services include outside human or machine monitoring.

4.4.2 Uses

The fraction of Jovians who will use these labs would be small except for the fact that Jovian secondary schools tend to teach at least a single required semester of engineering. Many of the common projects in these classes involve basic microgravity fabrication. Usually this is in one of two forms: a class renting braces of crystal fabricators for individual experiments, or a group project wherein the entire class is involved in the process of setting a microgravity alloy and machining it into a common part. With these programs in place the exposure of these labs to the general population is quite high.

From the perspective of the company renting the bays, secondary schools hardly account for a discernible fraction of their business. Most of their business comes from artists, researchers, and machine shops that find themselves lacking the proper facilities for a custom part. The ebb and flow of users is frustratingly unpredictable to the rental companies, who typically find a large portion of their facilities unused at any given time. Still, with aggressive marketing and cost-cutting measures, these facilities have remained profitable.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home